Though he’s a spiritually in tune emcee, Mick Jenkins’ patience didn’t come from piety. There was no humble decision to wait, only the wisdom to focus on a future beyond the immovable present. That’s why he sounds so hungry on his latest album, The Patience — his first free from a label deal that kept him financially and creatively pressed for the last decade.

His fourth studio album is a departure from the conceptually-dense projects that fans have come to expect from the Southside Chicago emcee. Rather than darting around a singular prompt with spacious metaphors, The Patience (which is out at midnight) is tense and tightly wound, held together by the cohesiveness of the energy that birthed it. On “Show and Tell,” Jenkins’ mind is in the present with fiery lyrics about finally cutting loose, while on “Smoke Break-Dance” he dips into his repertoire of smoking songs to flashback to how he kept his head down over the years. On The Patience, Jenkins is focused on making records, tapping into a potent and latent frustration that could’ve been mined by its very source, had he not held onto it until it could work for him.

“Patience — it’s not what a lot of people think, waiting. It is the capacity to accept delay, trouble or suffering without getting angry,” Jenkins tells Okayplayer during a Zoom call. “It feels like wisdom because I’m looking past all this shit.”

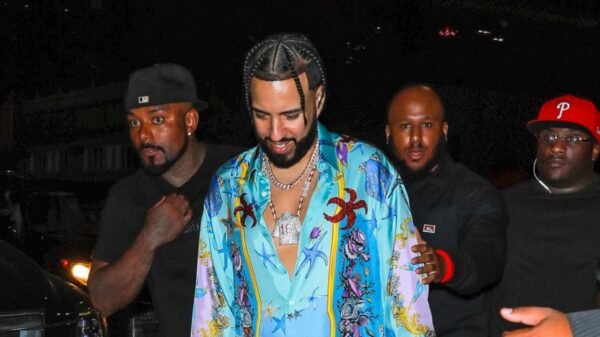

Photo by Bradley Meinz for Okayplayer.

No way out, only through

For the last nine years, since 2014’s critically acclaimed The Water(S), Jenkins had been releasing music in partnership with Cinematic Music Group. He agreed to a 50/50 deal in return for diminishing recording expenses across three albums: $90K for The Healing Component, and $60K for Pieces of a Man and Elephant in the Room.

“At that time, I was making albums for nothing. What do you mean $90K to make an album?” Jenkins said. “So then I got to a certain point where I’m trying to release my second album and we can’t do shit, because we only got $60K. No one’s making an album for $60K.”

It’s difficult to pin down the exact costs of recording an album but to put it in context, in 2011 NPR’s Planet Money estimated that recording just Rihanna’s single “Man Down” cost about $78K (throw on another million for marketing and promotion). Additionally, neither artist sees a single dollar from their recording until the label recoups its investment — in Jenkins’ case, seeing only 50 cents on every dollar after that recoup.

The financial pinhold left him feeling like his best work deserved better prospects. He didn’t have the budget or the incentive to shoot numerous music videos, package intricate rollouts, or tour widely under the limitations of the deal. And despite what he’d been told during signing, there was no negotiating a way into better funding or out of the contract.

“We spoke about how we would handle the deal if we ever wanted to part ways. And the specifics of what [they] said was different once I wanted to part ways,” Jenkins said. “To the point where [they] laughed in my face like, ‘I would never let him go like that.’ [They] said those words to me.”

So, Jenkins waited.

Mick Jenkins – Smoke Break-Dance (Feat. JID, Prod. By Stoic) [Official Music Video]www.youtube.com

“I don’t expect people to understand”

Fans gathered on a July 6 live stream in anticipation of the first single for The Patience — “Smoke Break-Dance,” his long-overdue joint effort with J.I.D. — were an even split between perplexed and excited in the chat when Jenkins said, “I wasn’t even trying to do my best for the last five years.” His words were more genuine than dismissive, less of a sudden realization and more of a decision he quietly made years ago.

Even under the mental and financial constraints of the deal, Jenkins established a reputation as one of the sharpest concept album writers in the genre. On The Water(S), liquid water became a metaphor for spiritual health — both as vital in abundance as withering in withholding. Pieces of a Man was a nod to Gil Scott-Heron’s 1971 debut studio album of the same name, following the depth of the poet’s quiet self-analysis in the face of a world that still puts Black men into boxes.

A skeptic would be right to question how such carefully spun metaphors and complete concepts could be the product of an underinvested approach. But Jenkins finds that, as a writer, following a theme or concept comes most easily.

“I’m a rapper, but I’m a writer. Words are it. Language is it. As a writer, as a poet, all I need is a prompt. If you tell me to just write, that’s difficult,” he said.

His most recent album, 2021’s Elephant in the Room, was a collection from a frustrated artist getting a few things off his chest and, as a goodbye to his contract, comes closest to where we find him mentally on The Patience.

“I think Elephant in the Room was venting. This is cleansing. It’s me after the cleanse. I’m ready to go back in and this [album] is the first thing I have to say,” he said. “I’m free. I’m out this deal. I’m not making no concept. Fuck a concept. I’m just making good music.”

There’s a reason that the burning of sage comes up several times on The Patience despite the absence of a conceptual through-line. Unlike previous projects, cohesion is found more in the power of manifesting a brighter future than in writing to a prompt. Mick Jenkins has been waiting almost a decade to put those years behind him.

For someone who radiates the competitive drive of a star player, the internal struggle to always be in top form bursts from the selection of tracks assembled from a vault built during years spent in the grip of that feeling.

“I’ve been telling people that they’ve been holding me back,” Jenkins said. “Doing more of the same, which is good, ain’t good enough.”

“If you’re telling us, while you’re averaging 15 points a game, that this team is holding you back. Well, when you get on a new team that gives you a longer leash, you can’t average 17,” he said. “We need to jump from 15 to 25. See what I can do? These motherfuckers had me coming off the bench!”

Mick Jenkins has waited almost a decade for this

With The Patience, he’s had the time. The records are noticeably more aggressive in vocal delivery, and more uptempo but tense in production than the Chicago emcee’s previous work.

Cinematic production emphasizes the use of live instrumentation, largely assembled by producer Berg, who was just credited for work on Noname’s bassline heavy Sundial-ender “oblivion,” and Stoic, a New York producer inspired by Alchemist and Madlib. The brass tones of saxophone and warmth of ivory keys are familiar beneath Jenkins’ voice, but there’s an edge to his delivery that feels modern and invigorated. Even on his most philosophical work, he’s always been an assertive rapper, calling it how he sees it rather than posing open-ended questions. That direct treatment put to classic braggadocio still effectively drives his point home. He’s not rhyming about cars or women. He’s been eating off features and happily married, but fueled by the feeling he’s coming off the bench. He’s here to show you what he’s been holding onto.

Jenkins pauses on the description “commercial,” before agreeing it’s something else. “I’ve always had desires for production to be bigger to sound bigger,” he said. “I don’t know what it is, it just feels good. It feels bouncing, it feels aggressive, you know?”

Within the first 10 minutes of The Patience’s 30-minute runtime, Jenkins brings out Freddie Gibbs, Benny the Butcher and J.I.D., features that today summon fan crossover and decorate debut albums. The kind of features that he’s never tapped previously, favoring calls to then up-and-coming artists close to the Chicago scene like Saba, theMIND and Noname. Chicago still has a highlight presence on the album though. On the flex cut, “Farm to Table,” Vic Mensa’s verse about the success of his cannabis company, 93 Boyz — the first Black-owned brand in Illinois — is one of the best. But it’s set up perfectly by Jenkins’ own newfound power over independence.

Since getting out from under his previous deal, he’s decided to pursue one-off contracts. The Patience is being released in partnership with RBC Records and BMG, a partnership which he described as parallel to leaving a toxic relationship for someone who treats you well and “you don’t know how to act.” Jenkins said that the cost of the features on The Patience alone surpass the $60K budget of his last two albums.

“I’ve been in the studio with n***as. I made music with people that was not allowed to come out. There’s all these different variables as to why I haven’t been allowed to have ‘bigger’ features over the years,” he said.

“I think it’s something that fans notice,” he added. “There’s a pipeline for new artists that when they hit certain benchmarks you should start to see certain things and when you don’t, it starts to form your opinion about their trajectory.”

Opinions about trajectories are often informed by rap media — the current state of which catches more than one barbed rhyme on the album. In 2015, Jenkins was passed up for a significant benchmark in the XXL Magazine Freshmen Class, despite The Water[S] widespread acclaim the year before and even meeting with representatives about the cover.

“I thought we were going up there to meet [them],” he said. “I know how to embellish myself, but I wasn’t doing any of that. I was being real. I didn’t know I needed to be doing any of that.”

Jenkins became jaded with label pocket-watchers and rap media politics. He celebrated the artists around him reaching new heights while he remained constrained by a situation that grated against his competitive artistic drive.

“You’re in limbo. You’re in the middle of something that you need to fix that you can’t fix,” he said. “A lot of times people think negative spaces produce great art…”

“It’s so hard for people to find contentment and happiness that people don’t realize how much more powerful that is in stoking a creative flame,” he continued. “I actually operate my best, when I’m happy, when I’m clear-headed. Being exploited and being aware of it is probably one of the worst things that can happen for your creativity. You start making your art to meet the requirements of the exploiter and not to create from the heart.”

The Patience ends with a direct address that bookends the album with a reflection from that less frustrated place. The wisdom is indicative of the distance he’s gained from the claustrophobic energy that drove much of its recording. “I’m just now stepping into what I feel like is full agency over my creativity, my artistry, my business and myself as a man,” he says on the outro.

This is why an album titled The Patience explodes with such forward momentum. Much of it was recorded during these intensely frustrating years, but it was always planned that it would serve a brighter future.

“The music sounds like my patience,” he said. “And I don’t think it sounds patient.”

Read the full article here